Women in the creative world are finally getting some of the recognition they deserve — at least in the cultural domain.

This fall alone, expect one of the most comprehensive new books on female designers, a book about the unsung heroines of graphic design, and a book about designing motherhood. In London, the Tate Modern is doing a retrospective of Swiss renaissance woman Sophie Taeuber-Arp (the exhibition will go to the Museum of Modern Art in November). And in Weil-am-Rhein, the Vitra Design Museum is showcasing over 80 women who have the shaped the furniture, fashion, industrial, and interior design worlds over the past 120 years.

The outburst of attention coincides with a series of anniversaries around women’s right to vote between the 1900s and 1920s (although for years in the U.S., voting rights would largely only apply to white women). The Vitra exhibition, titled Here We Are! Women in Design 1900 – Today, seeks to redress a male-dominated history by exploring the role women have played in the design world against the backdrop of gender equality movements of the 20th and 21st centuries.

For many women highlighted in this exhibition – and in the flurry of books we’re seeing on the subject – acknowledgement comes almost a century late, but it brings long-overdue recognition that is essential for the next generation of designers. Lest we forget, women make up over half of designers today, yet discrimination and gender bias continue to plague the industry. In 2019, women held only 11% of leadership roles in the design field.

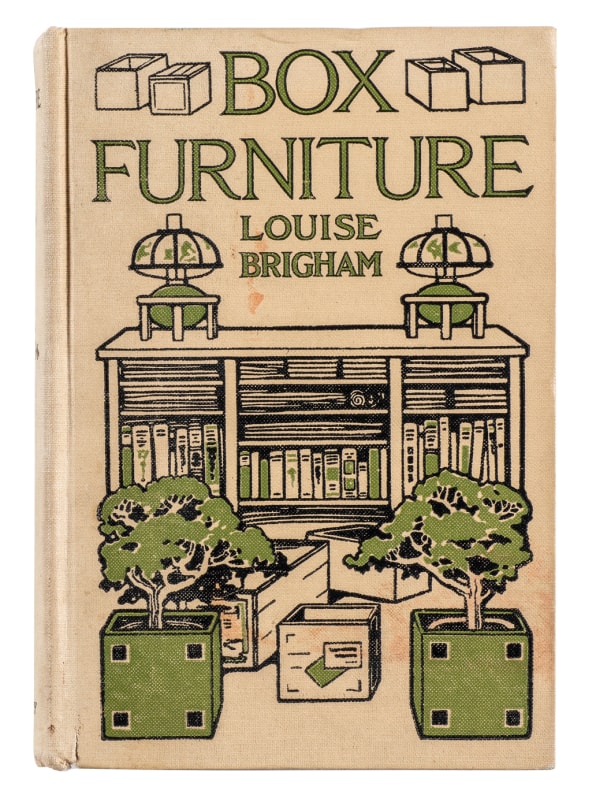

“The development of design as a practice as we understand it coincides with the time where women get a lot more rights,” says Viviane Stapmans, who curated the Vitra exhibition along with Nina Steinmüller and Susanne Grane. This bid for emancipation is reflected in the design produced in the early 20th century. In 1909, Louise Brigham pioneered the DIY movement with her book Box Furniture, a manual for amateur furniture makers. And some years before that, Jane Addams successfully lobbied for better urban sanitation, more playgrounds, and kindergartens throughout Chicago. Addams’s work would be described as social design today, but Stapmans says her contribution to design is unqualified.

Throughout the years, many women collaborated closely with their male partners, but few got the same recognition. Aino Aalto, for example, was long seen as the muse of Alvar Aalto, the Finish architect and key figure of midcentury Modernism. But Aino worked closely with her husband and was one of the pioneers of Scandinavian design (the exhibition showcases her pressed glassware collection, which was inspired by ripples in the water).

The road to equity has been long and winding, perhaps best symbolized by the visionary architect Denise Scott Brown’s decades-long quest for recognition alongside her partner, the influential architect, Robert Venturi. Denise Scott Brown is regarded as one of the most significant architects of the 20th century, both through her architecture and seminal writings, yet she was often overshadowed by her husband.

Despite her struggles, which she outlined in a poignant 1989 essay, Scott Brown never stopped working (she retired in 2012 and is now working on two books). Sadly many others did. Flora Crawford, whose solid steel cantilever chair is displayed in the exhibition, worked in a creative partnership with her husband before she turned to art, “which we’ve seen a few times,” says Stapmans. “It doesn’t diminish the contribution they made, but it may be a reason why they’ve been overlooked.”

The sad truth is that much of these women’s work has not been documented with the same gusto and perseverance as their male counterparts. According to Libby Sellers, a design historian and curator who also wrote Women Design in 2018, some women got married and stopped practicing, while others took their husband’s name, which made them more difficult to track.

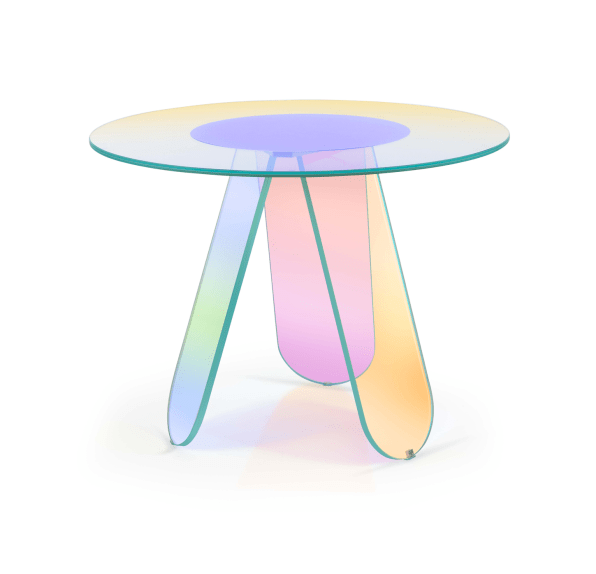

Sometimes,

she says, language got in the way. The Japanese furniture designer Hasako Watanabi has produced a wide range of custom interiors and sculptural furniture and lighting designs, but very little information is available in English. (It’s unclear whether the same applies to male foreign designers.)

And sometimes, history unraveled in ill-fated ways. Lilly Reich was one of the first women to teach at the Bauhaus, where she directed the interior design workshop in 1932. Sadly, the Bauhaus was closed shortly after by the Nazis. A decade later, her studio in Germany was bombed, wiping away many archival documents. (She did have the foresight to box up 900 of her own drawings and 3,000 of those by Mies van der Rohe, a long-time collaborator and one of the pioneers of modernist architecture ; they can now be seen at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.)

But perhaps the worst offender of it all has been the pure neglect that some female designers have been subjected to. Minette de Silva was a pioneer of Sri Lankan modernism and the first Asian woman to become an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects, yet her studio and home in Kandy have fallen into ruin. “Sadly a lot of her built work was not documented in Sri Lanka and was lost to ravages of time and nature,” says Sellers.

To some, the outpouring of recognition that female designers have seen in the past years may seem like it’s too little, too late, but for Sellers, there is a real sense of urgency to this movement. “It’s time to address the balance while they’re still alive, or while their works are still accessible,” she says. “Unless you are visible or being documented or being discussed, it’s all too easy to forget about it.”

There’s also something else. The more women are recognized, the more visibility they get in the eyes of the next generation. “Role models are really important,” says Sellers. “They have a statistically significant impact on women’s performance in all fields.”

More Stories

Choose a Best Home Which Fits on Your Budget

Protect Your Home by Choosing the Best Roofing Contractors

Design Guide: Creating the Perfect Home Office